Worst Manager Ever

Many years ago, I was part of a growing team of software developers at a start-up on the West Coast. We were getting too big to fly by the seat of our pants, so we hired a development manager to implement the formal processes a larger team needs.

The developers didn’t really participate in the hiring process. The decision was left instead to the higher-ups. Though the person taking this position was supposed to participate in architecturul discussions, write code, and do code reviews, the person they wound up hiring said he was interested in none of that.

He was primarily a marketing and sales type, and he insisted on being given the title of Vice President of Engineering. That was not the title of the position, but the company changed it to suit him. So from here on, we’ll call him The Veep.

When The Veep came on board, our dev team had no rules. We didn’t document software specs, except on a whiteboard that anyone could erase. We had no formal release process and no unit or integration tests. Developers deployed code to production systems whenever they wanted, without telling anyone. We didn’t tag releases, and no one knew which version of what software was running on what server.

Our main way of testing was to deploy new code to the production systems of our low-value customers and then sit back and wait for them to tell us what blew up. Low-value customers were often poorly-funded non-profits who couldn’t afford to ditch us.

Planning and scheduling were pointless because we spent all our time putting out fires. If a bug appeared in a production system and we couldn’t reproduce it on our dev machines, we’d edit code directly on the production server. Once we got it working, we’d copy the code back into source control.

The Veep read a book on Agile development and decided that’s what we were already doing, so nothing needed to change.

At the time, the company had one product and many custom-built projects. I had spent the past few years writing most of those projects, which all had similar features. People kept paying us $100,000 or more to custom build variations of the same system. As word of mouth spread, more people wanted their own version of that system. With customers already lined up, we realized this would be product number two.

Since I had already written six or seven versions of this system, I knew all the features, I understood the architecture, and I had a throrough knowledge of the domain-specific requirements and all the gotchas that had bitten me in early iterations of the software.

The company said, “Sit down and spec out this product, then you’re going to lead the team that builds it.”

Perfect, I thought.

By this time, I was working on the East Coast and the rest of the team was on the West Coast. As I was drafting and revising the spec, many water-cooler conversations were happening in the office without me.

On our formal calls, I’d go over specs with the team, and The Veep would assign different tasks to different developers. Early on, while discussing part of the system core, I told The Veep that this piece would take around eight weeks to write.

“No it won’t,” he said. “Speed Racer wrote the whole thing in five days.”

“What?”

Speed Racer was an on-site developer who wrote code as fast as he could type.

“He better not have,” I said, “because there’s six years of domain-specific knowledge in that code that he doesn’t have. There’s no way he could write that to spec in five days.”

“Yeah, well, he did. While you’re farting around with that stupid spec, he’s getting shit done!”

When I looked at the code, I just shook my head. It was a single method containing thousands of lines of code. I called Speed Racer and said, “What the hell is this? There’s like four hundred if/else blocks in here, and some of them are nested twelve deep.”

He said, “Yeah, I know. It’s pretty elegant.”

“How is that elegant?”

“All the business logic is rolled into a single method. You just call that and you’re done. Software doesn’t get much simpler than that.”

The code was riddled with assumptions that violated the spec, but Speed Racer insisted it was correct and the spec was wrong.

I called The Veep and told him about the problems. I told him I needed eight weeks to rewrite the code correctly.

“Why would I let you waste eight weeks rewriting code that’s already working?”

“Because it’s not working,” I said. “I can tell you right now all the ways this code is going to fail.” And I proceeded to list out the problems and how they would manifest.

He was unswayed. But a few weeks later, he came back to me and said, “You were right. We’re seeing the exact failure scenarios you described. I want you to go in and fix that code.”

While I was doing that, The Veep had Speed Racer crank out as many features as he could. As I cleaned up his initial mess, I browsed through his commits and saw more and more bad assumptions, more brittle, highly-coupled components, more violations of the spec. Each time I looked at a commit, I knew exactly what I’d be fixing a few weeks down the road.

Sure enough, The Veep would call and say, “Hey, drop whatever you’re doing. I need you to fix this stuff Speed Racer added a couple weeks ago. It blows up every time a user makes a mistake.”

“Why can’t he fix his own code?” I asked.

“I don’t think that’s a good use of his time. The guy’s a fucking machine. I don’t want to slow him down.”

For months, I was the architect and lead developer, and my job was to fix the junior developer’s mistakes. This made me miserable. I brought it up many times with The Veep, but it was pointless. From his perspective, everything was going great.

Looking further ahead, I imagined this code going into production and all the fires we’d have then. There was no way in the world I was going to sign up for another year of daily emergencies. We simply couldn’t release another product without formal testing.

So I started writing unit and integration tests. I wanted to assure myself that the essential features were working, and that new code wasn’t corrupting data or introducing regressions.

Every time Speed Racer committed code, he’d send me an email saying, “Dude, your tests are broken again.”

The other developers took the same attitude and eventually they complained to The Veep: those damn tests were a menace.

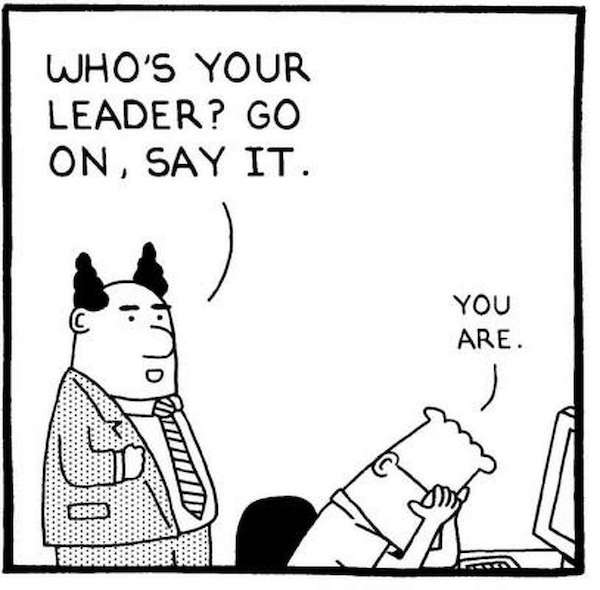

The Veep called me into a meeting where he and the entire team confronted me. It was like an intervetion where a bunch of people confront an addict and force him into rehab.

The Veep said, “You need to rip all the tests out of the codebase.”

“Why?”

“Because they break the build.”

“I’m not releasing another product without a test suite.”

The Veep shook his head. “You’re going to remove the tests,” he said. “Right now! Open your laptop and delete the code. You’re not leaving this meeting until that happens.”

I did what he said.

I had been approaching my breaking point for months, and this was the second-to-last straw. My hair was falling out, and a friend who noticed that I was always stressed out said, “You should talk to this CTO down the street. He runs a really tight ship and makes sure his developers have everything they need to do top-notch work.”

A few days later, I was turning that over in my mind as I reviewed a cascade of recent commits. Speed Racer had ripped out some fundamental architecture all the way down to the database level. The deleted code had allowed customers to run mutliple projects on a single installation. Now they could run only one.

Speed Racer and The Veep had two different justifications for this change. The Veep said, “Now customers won’t have to go through that annoying step of choosing which project to work on.”

Speed Racer said, “The system is much simpler now. All the code can assume the user is working on project number one, because that’s the only project there is.”

Looking further, I found a dangerous assumption that permeated every level of his code. He assumed that all data would be submitted to the system in a fixed order, and that no data would ever be missing. I knew from experience in the domain that data would be submitted in unpredictable order and that missing data was common. (Customers often collected data on paper and entered it weeks later.) My spec said explicitly that the system must accomodate this.

I called The Veep and warned him that customers would reject the software because it could not accommodate missing or randomly-ordered data submissions and because Speed Racer’s architectural “simplification” made it impossible to run more than one project on a single installation.

The Veep said, “You’re always so negative and Speed Racer is always so positive.”

The company was about to roll this system into production with a handful of clients. I knew if I stayed on, I’d spend months fixing critical bugs. And I’d be doing it under the gun, probably on a live production system while angry customers complained because their projects were dead in the water.

In fact, this is what I had been doing for years: working 70-hour weeks in constant emergency mode to fix issues that a decent test suite would have prevented from ever reaching production. The whole point of hiring the Veep was to end this madness so the dev team could be more productive.

I printed out my résumé, walked down the street in the pouring rain, and handed it to the CTO my friend had told me about.

“Here,” I said. “If you’re looking for a developer, give me a call.”

Then I turned around and walked out.

The new software went into production. It crashed a lot and made customers angry. Some of them were really angry, having to pay a large staff that had nothing to do because “the system was down,” sometimes for days at a time while our team worked frantic overtime to try to fix it. Even when the system worked, the single-project limitation and strict data-submission ordering requirement led to constant complaints.

The Veep called and said, “I need you to toss in a couple of fixes. Customers need to run multiple projects and you have to flip some switch to make the system handle missing and randomly-ordered data submissions.”

Translation: Re-architect the app and root out the nine-hundered hard-coded assumptions of strict ordering.

“How long do you think that’ll take?” he asked.

“Months,” I said.

“Yeah, well it needs to get done this week. We got people breathing down our neck.”

By this point, I had had both formal and informal interviews with the CTO down the street. He told me he was working on an offer, but salary was a sticking point. After hanging up with The Veep, I called the CTO and said, “How close can you come to matching my current salary?”

He said, “Within five percent.”

“OK, I’m in.”

He brought a contract by that afternoon. I signed it and put in my two weeks' notice.

After I left the company, all the other developers followed suit. As one of them told me, “I kept waiting for management to do the right thing, and they kept not doing it.”

I ran into The Veep a few years later and asked him how things were going with the team, knowing that none of the original members were still there.

“Oh,” he said. “We got rid of them.”

“But you’re a software company!”

“Yeah, developers are the worst part of this industry. They’re expensive as hell and all they do is complain. Now I just pick up college students on contract. They’re cheap and they’ll work all night. It’s so much better this way!”